Pages

4.30.2009

Gusky on Phishing

Read Hrag on Jerry

On the NYFA site, Hrag Vartanian reports on Jerry Saltz's talk at the New York Studio School on April 22.

On the NYFA site, Hrag Vartanian reports on Jerry Saltz's talk at the New York Studio School on April 22.One problem with art in the past 15 year is that over-academicized critics and curators have taken the joy out of art. Another was the overheated art market.

Quoting Vartanian quoting Saltz: “The problem with the art market,” Saltz said . . . “was that we were all in the same boat. We can only hope that this future art world would probably look like a massive fleet of modest-sized ships, rather than one ill-fated luxury ocean liner." Read the whole thing.

Picture from the NYFA website

4.27.2009

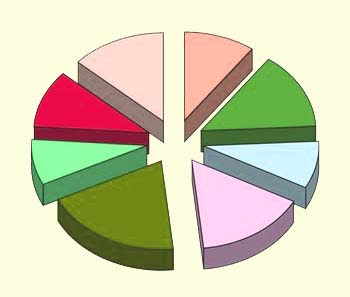

Marketing Mondays: How is Your Pie Sliced?

I purchased a specially vented air conditioner for my studio last year from Grainger, the machine and equipment company. I’m now on their mailing list. The way they address the envelope makes me laugh every time I get one: “Joanne Mattera, Facility Maintenance Manager.”

Yes, that’s me. Joanne the Janitor. I’m also the CEO, the head of PR, the administrative assistant, the secretary, the director of the accounting department, and the entire staff of both the mail room and the packing and shipping department. It's quite a pie; I might as well be a baker, too.

I’m telling you this for a reason.

Last Monday I was the visiting artist at Marywood University in Scranton, Pa. I was invited by the painter Steven Alexander, a professor in the art department. My slide talk—to undergraduates, MFA candidates,

Last Monday I was the visiting artist at Marywood University in Scranton, Pa. I was invited by the painter Steven Alexander, a professor in the art department. My slide talk—to undergraduates, MFA candidates,.

The pie chart: Guess how much of my time

is actually spent painting

.

and faculty—was a career overview intertwined with practical career advice for the students. Steven had introduced me as a working studio artist, and during the presentation, as I showed my work and discussed career issues, I talked about my transition from 9-to-5 employment (when artmaking was squeezed into evenings, weekends, vacations and "sick days") to full-time studio artist. .

.

This audience was with me, so I went on for a whole hour. When the lights went up, the questions came out. Great questions, too: specifics about finding a gallery, understanding the gallery hierarchy, pricing work, studio issues, and balancing the art practice with income-producing jobs.

.

Toward the end of the Q&A period, a professor sitting at the back asked: "What percentage of your day now is actual painting time, as opposed to when you were working a full-time job?"

.

Here’s the shocking answer: About the same. I’d guess about 30 percent, or the amount depicted by the three saturated wedges of red, aqua and olive in the pie chart above.

.

The rest of it is taken up with all the non-painting tasks required to get the work out into the world and to keep track of it once it's out there. Of course the math doesn’t usually work out so neatly. When I’m preparing for a show, I might spend almost 100 percent of my work time in the studio for weeks or months, and when the show is delivered, 100 percent of the following weeks crashing, then cleaning up and catching up. But that professor’s question is a sobering reminder that in the phrase “working studio artist,” working is the operative word. When I left nine-to-five, I traded 80 hours a week (40 with with steady income, health insurance and vacation time) for 80 hours with an unpredictable income and no bennies.

.

I wouldn’t want to go back to the way it used to be. I've been a painter for long enough now that when I go into the studio to paint, I paint. (That 30 percent goes deep. ) And all the non-painting work is in service to my career, not an employer's business. Having a fully immersed art life means that, in addition to the administrative work and facility maintenance managing, I'm also making studio visits and seeing art, writing and thinking about art. I actually like the way the pie is sliced. (Well, except for that dreaded desk work.)

.

Now let me take the role of the professor: What percentage of your time is spent actually making art? Or to recast in a more visual way: How is your pie sliced? And are you happy with the portions?

.

4.24.2009

Sol LeWitt at MoMA

.jpg)

I haven't yet driven up to the big Sol LeWitt show at Mass MoCA, but there's plenty of time for that. It's on for another 24.5 years. Instead, I popped into the LeWitt installation at MoMA, which continues only until June 1.

Wall Drawing #260 is in an open space on the fourth floor, a big modernist box with wall-to-wall windows overlooking the sculpture garden. The other three walls, all broken by doorways, nevertheless offer high and broad expanses for the work, which is in the museum's collection.

I like this chalk-on-painted-wall piece, all arcs and curvy lines bisected or otherwise divided by angles and staccato lines. There's a logical progression to how the lines intersect, but I'm an artist, not a mathemetician, so I'm less concerned with the precise peregrination of the line, only that it moves and morphs as your eyes travel from wall to wall. The linear geometric composition suggests nothing so much as choreographic notation--a formal expression of the human activity in the enclosed space as people pass into, around and through it.

.jpg)

With your back to the window, you turn to the left wall, which contains a legend for the visual logic of the work

.jpg)

.jpg)

.

4.20.2009

Marketing Mondays: Stayin’ Alive

With the “For Lease” and “For Rent” signs popping up in Chelsea and SoHo, the smug schadenfreuders are told-you-so-ing even as the ground gives way beneath their feet. Of galleries that have not closed, many are letting staff go—reportedly, even Pace and Gagosian. Red dots are everywhere less in evidence.

With the “For Lease” and “For Rent” signs popping up in Chelsea and SoHo, the smug schadenfreuders are told-you-so-ing even as the ground gives way beneath their feet. Of galleries that have not closed, many are letting staff go—reportedly, even Pace and Gagosian. Red dots are everywhere less in evidence.But the will to survive is strong. Whether the soundtrack is the BeeGees—oh, oh, oh, oh, stayin’ alive, stayin’ alive—or Gloria Gaynor’s evergreen anthem to perseverance (or Celia’s Cruz’s inspired version in Spanish), we are all, as Celia sings, sopraviviendo. Surviving. Or trying to.

Galleries

At least Five galleries in New York have come up with novel ideas to keep going strong:

.

. Winkleman and Schroeder Romero, those side-by-side dynamos over by the Hudson on 27th Street, have come up with Compound Editions, a project that offers limited-edition prints, sculptures or cards at acquisition-friendly prices (so far, in the 100-$150 range). The series are selling out, such as All Your Eggs, by Andy Yoder, shown left, an edition of 100. (Disclaimer: I bought one.)

. Winkleman and Schroeder Romero, those side-by-side dynamos over by the Hudson on 27th Street, have come up with Compound Editions, a project that offers limited-edition prints, sculptures or cards at acquisition-friendly prices (so far, in the 100-$150 range). The series are selling out, such as All Your Eggs, by Andy Yoder, shown left, an edition of 100. (Disclaimer: I bought one.) .

.

. Invisible Exports, down on Orchard Street, offers its Artist of the Month Club; pay $2400 for a year's subscription and you'll get a limited-edition print from a curator-selected artist each month. The collectors will know who the curators are but not the work they will select, says Benjamin Tischer, a director of the gallery. The website describes the process as introducing "Duchampian chance into the act of collecting."

. Invisible Exports, down on Orchard Street, offers its Artist of the Month Club; pay $2400 for a year's subscription and you'll get a limited-edition print from a curator-selected artist each month. The collectors will know who the curators are but not the work they will select, says Benjamin Tischer, a director of the gallery. The website describes the process as introducing "Duchampian chance into the act of collecting.".

. In Williamsburg, Jack the Pelican Presents has installed Old School, a salon-style show of work by gallery artists and others. The paintings, works on papers and sculptures--all small--are priced to sell. Everything is under $2000, and many works are in the modest three figures. Cash and carry is the operative mode, with new work installed as sales are made. The gallery features work primarily of emerging artists, and in this economic climate it's a chance for the work to be seen as well as sold. The show runs through April 26.

. In Williamsburg, Jack the Pelican Presents has installed Old School, a salon-style show of work by gallery artists and others. The paintings, works on papers and sculptures--all small--are priced to sell. Everything is under $2000, and many works are in the modest three figures. Cash and carry is the operative mode, with new work installed as sales are made. The gallery features work primarily of emerging artists, and in this economic climate it's a chance for the work to be seen as well as sold. The show runs through April 26..

. Metaphor Contemporary, the gallery run by painters Rene Lynch and Julian Jackson, also in Brooklyn, has invited artists to donate a piece that will be part of a group exhibition and silent auction at the gallery in May (and an auction component that will take place on line). The show is titled Stayin' Alive. They've given artists the option of receiving the usual percentage of the sale, or something less, which would put more money into gallery programs. It's unusual, but artists who have shown there--I'm one of them-- are pitching in. (And thanks to the gallery for the title to this post; I unconsciously plagiarized it from them. ).

.

Artists

Artists have their own ways of keepin' on keepin' on. Some are holed up in the studio painting more than ever. Some are focusing more on works on paper than on painting, or small paintings rather than large. Some are participating in group shows rather than committing to solos, or taking the opportunity to show at venues they might not have considered before: open studios, art centers, private dealers, even some non-profit venues where everyone kicks in a couple hundred to cover expenses (but not vanity galleries).

.

I haven’t painted for a couple of months. Instead, I’m working with my network of galleries to place work that has already been made. For some time I’ve been trying to get off the treadmill of “What do you have that’s new?”—as if work from two years ago isn't as good or important as the new piece whose paint is not yet dry—and this downturn has given me that opportunity. I’m pleased with the sales, and I think my collectors are pleased with the work they've acquired. I’m also catching up on a ton of administrative work (and, if you haven’t noticed, blogging a little more than usual). I’m seeing more art, making more studio visits. When I get back in the studio—which will be soon, soon—I’ll do so with energy, enthusiasm and optimism.

.

So here’s what I want to know from you, artists, gallerists and others: What are you doing to stay alive?

.

4.15.2009

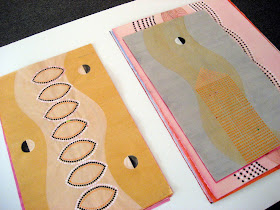

Grace DeGennaro: Wellspring

.

.Is there anything more thrilling than looking at a painter's work on paper? Not for me. As painters we approach paper differently--more primally. Or perhaps with fewer filters. We let more out onto the surface. So being privy to page after page of a portfolio is--how do I say this without it sounding corny?--like being washed over by the stream of an artist's imagination. At least that was what I was thinking when I had the opportunity to see Grace DeGennaro's portfolio at Clark Gallery in Lincoln, Mass.

I went on the last day of the Maine-based artist's exhibition, Return to the Source, which consisted primarily of paintings. It was a beautiful show, whose images--rivers and vines, diamonds, fountains and phases of the moon--come right from the work on paper, which come from traditional symbols and sacred geometry, which in turn spring from, as DeGennaro puts it, "ideas that lie beyond the limitations of language and culture." If I were to put a few words to the work, I'd say life, growth, renewal, time. I suppose it was appropriate that I went just as the earth was making its temporal transit from winter to spring.

The artist showing her portfolio: Her vocabulary of symbols, from the sacred geometry of many cultures, is realized in gouache on translucent okawara or heavier watercolor paper. Viewing it felt like a meditation

.

.

..

.. .

. .

. ..

.. .

.

You can see more of DeGennaro's paintings and work on paper on DeGennaro's website, the Clark Gallery , Aucocisco Gallery and Geoform

.

4.13.2009

Marketing Mondays: Promotion

Boston sculptor Donna Dodson asked the question that prompted this week’s topic:

“I was wondering about self-promotion versus promotion through a gallery. Do these work together or do they conflict? What are the boundaries?”

“I was wondering about self-promotion versus promotion through a gallery. Do these work together or do they conflict? What are the boundaries?”

.

As a self-promoter with a wonderful network of galleries supporting me, I can answer this one with confidence. The short answer: Self promotion and gallery promotion go together, hand in glove.

A slightly longer answer: Communication between you and your gallery will tailor the fit. A smart dealer understands that the efforts you take on your own behalf will ultimately benefit the gallery too.

Here’s Valerie McKenzie of McKenzie Fine Art in Chelsea: "It's always enormously helpful when artists participate in the promotion of their work, and by extension, promotion of the gallery. So it's important for artists to maintain as broad and meaningful a professional and social network as possible."

Do you have a website or a blog?

Then you’re self promoting. If you are represented, provide a link to the gallery. If you should be contacted by someone who has found your website and likes the work, direct them to the gallery.

It would be a mistake to think, “This collector found me through my website so I’m going to make the sale myself.” If you’re represented, work with your dealer. If you work with several galleries, direct a potential client to a) the dealer closest to them, or b) if they have seen a specific piece they really love, to the dealer who has that work.

Once you direct the collector to the gallery, it is the dealer who will complete the sale, collect the sales tax, deliver the work. It may well be that as a result of this kind of attention, you’ll get the solo you’ve been wanting, or the ad to go with the solo, or a catalog raisonne of the show. Success breeds success. On the other hand, if you find that your website is consistently directing more sales to the gallery than the gallery is generating on its own—and you’re getting no perks, such as a nic(er) ad or a catalog—it may be time to renegotiate the relationship. Perhaps you can suggest that the gallery take a smaller commission on those sales. Or maybe you'll realize it’s time for a different gallery. (Another topic for down the road.)

Once you direct the collector to the gallery, it is the dealer who will complete the sale, collect the sales tax, deliver the work. It may well be that as a result of this kind of attention, you’ll get the solo you’ve been wanting, or the ad to go with the solo, or a catalog raisonne of the show. Success breeds success. On the other hand, if you find that your website is consistently directing more sales to the gallery than the gallery is generating on its own—and you’re getting no perks, such as a nic(er) ad or a catalog—it may be time to renegotiate the relationship. Perhaps you can suggest that the gallery take a smaller commission on those sales. Or maybe you'll realize it’s time for a different gallery. (Another topic for down the road.)

Are You Showing in an Open Studio?

If you’re gallery represented, you really don’t need to go the Open Studio route anymore, but if it’s one of those yearly events that your studio building or artists’ community participates in, go ahead. Cross promote with the gallery, working out ahead of time how you will deal with a sale. It might be as simple as calling the gallery to have them complete the sale over the phone--they take credit cards; you probably don't--or you having the collector make out a check to the gallery. Let the gallery deal with the business issues and the sales tax. The gallery will also maintain the relationship with the new collector in ways it’s set up to do: previews, special events, regular newsletters and such. And the signal to the new collector is, ‘If you want more work from this artist, come see it (and buy it) at the gallery.”

Having a Gallery Exhibition? Coordinate Your Efforts

Why duplicate when you can coordinate? If your gallery has exhibition PR taken care of, maybe you send a short handwritten note to a few critics or curators, inviting them to come to the show. Announce the show on your website or blog, again providing links to the gallery. Or maybe you promote yourself in an area outside the conventional parameters of gallery PR: your local paper, if it’s not in the same city as the gallery; a national publication whose demographic is specific to your identity or interests; even to your personal groups that might not go to a gallery if not for the fact that you re showing in it. "Tap into your network," says McKenzie.

Are You in An Exhibition Outside of the Gallery?

If you’re actively working on your career, it would be unusual if you didn’t show outside your gallery once in a while. It could be a solo or group effort, an invitational exhibition or independent curatorial effort, in an academic gallery, a non-profit, a co-op, or a regional museum. Depending on the circumstances, it might even be in another local/regional commercial gallery. Make sure your primary gallery (or the one that has facilitated the delivery of the work, or the one closest to the venue) is identified as representing you. For instance, I’m in a group show right now in a museum on Cape Cod. I have made sure that the work is identified as Courtesy of my gallery in Boston.

.

You should know under what circumstances and for how much your primary gallery will share in the exhibiting gallery's sales commission if work is sold. A contract will spell this out. Since most of us don't work with documents beyond a consignment list, or a contract for a specific show, it's essential that you have a conversation with your dealer. (My feeling is that if you secure the show and the dealer will get a commission from the sale, that dealer should cover the cost of shipping the work if the second venue doesn't. I have also found that in galleries outside of New York it's unusual for the dealer to expect a commission on a show you secure on your own.)

Take Initiative

A few years ago I had a modest retrospective of 10 years' of encaustic painting at an academic gallery. It was the kind of show that my dealers were unlikely to put on, since much of the work had to be borrowed back from collectors, but all of them were excited for me. That being the case, I worked with the director of the academic venue to create a catalog of the show—and I asked each of my dealers to pre-purchase 100 copies of the catalog at cost. I got a great catalog for my time and effort, and they got many copies of a catalog at cost, which they were free to either sell or give away to collectors. Everyone was happy.

Or maybe you’d like a bifold or trifold card when all the gallery is prepared to pay for is a postcard. It happens. Most galleries don’t have your personal self promotion built into their budgets. Maybe you design it. Or split the cost above a certain amount, or you pay for the essay if they pay for the catalog. Or maybe all your self promotion has brought your career to the point that they take on the cost of the catalog themselves. There’s no hard-and-fast rule here, so a request, a discussion, some give and take, may result in some or most or all of what you ask for.

If you’re in a group show at a venue outside your gallery, I think you are perfectly free to make up a postcard with your own work and name on the front, with back-matter info that says you are participating in a group show. If appropriate, include the name of the juror or the curator, and if it’s a small group, it would be a generous gesture to include the names of the other artists. Some galleries have a “Gallery News” section on their websites noting the activities and events in which their artists are participating. If not, they may be willing to keep a stack of cards at the gallery. Again, if you’ve indicated that your work is Courtesy of that particular gallery, it’s a nicely reciprocal promotional opportunity.

Apropos of promotional postcards, McKenzie suggests you distribute them judiciously: "I discourage the obnoxiousness of handing out your own announcement card at someone else's opening! "

Unsure of Your Parameters? Talk to Your Dealer

The artist/dealer relationship may have its roots in business, but as a relationship it is interpersonal. And in any interpersonal relationship, communication is essential. Bottom line: It’s a rare (and myopic) dealer who doesn’t welcome your own promotional efforts.

Artists, how have you handled this issue of promotion? And as always I’d love to hear from folks who have a different take on the topic—that’s you, dealers and curators. .

.

4.10.2009

Thornton Willis at Elizabeth Harris Gallery

Stephen Haller: Remembering Morandi

Warrior, 2008, oil on canvas, 70 x 59 inches; Flash Back, 2008, oil on canvas, 83 x 61 inches

.

On the face of it, Thornton Willis’s “lattice” paintings are exactly what you see: hard-edge grids with a slight visual overlapping, as wide bands of color float over or dip behind one another. The construction depicted is as old as human culture, used in physical form for baskets and cloth.The paintings take liberty with this structure, challenging our spatial perceptions of foreground and background, of what’s smack up against the picture plane and and how that relates to deeper, more ambiguous space. Their proportions, vertically oriented and of roughly human height, function as a kind of visual window into which you can fall, taking your perceptions with you. It’s a thrilling sensation, not unlike standing at the edge of a cliff—although your ideal viewing distance is about six feet away.

Each painting is a variation in color and structure. Even when several paintings have the same long rectangular proportion, the placement and structure of the bands—and certainly, their color, often modulated rather than flat—change, along with their individual cadences and rhythms. Looking at them in this way, music rather than textiles would seem to be the touchstone for the work.

Up close there’s another perceptual shift. What appear initially to be hard-edge paintings are in fact emphatically handmade with wavering lines and unexpected drips, pentimenti, and often a vigorous, textural overpainting. There’s a catalog photograph of Willis standing before an in-progress painting that’s taped where the colored bands are laid down. That must have been early in the process, because it’s only after the tape comes off that things get really interesting.

.

.

Warrior in foreground; Blue Sky with Lattice and Trellis in the Sun, both 2008, oil on canvas, 61 x 34 inches

Warrior in foreground; Blue Sky with Lattice and Trellis in the Sun, both 2008, oil on canvas, 61 x 34 inches Peeking around the corner, Flash Back, a detail of which is shown below

Peeking around the corner, Flash Back, a detail of which is shown below

The show is up through April 19 at Elizabeth Harris Gallery in Chelsea. See more on the gallery website.

.

.

4.08.2009

Julie Evans at Julie Saul Gallery

.

If I blogged for a living, I'd be much more timely with my posts. But my commitment to Marketing Mondays and um, that other thing I do, limits what and when I post.

Before any more time goes by, however, I want to show you a few images from a beautiful show that's up through this Saturday, the 11th: Julie Evans's Lesson From a Guinea Hen, at Julie Saul Gallery. Evans was in the gallery when I stopped in to see the show a few weeks ago. There we met for the first time (though we are Facebook Friends with many mutual friends in cyberspace and real life). .

.

4.06.2009

Marketing Mondays: Reciprocity

.

My friend Susan is a great example of how reciprocity works. A midcareer artist with a long resume, she understands how to network and she has the contacts to do it well. Because she’s secure in her career, she knows that sharing information or recommending someone will not diminish her achievements. On more than one occasion she has given my name and website to one of her dealers. I have done the same for her. Result: I’m with a gallery on her referral, and she on mine. We’ve each expanded our careers that much more by the simple act of mutual support.

My friend Susan is a great example of how reciprocity works. A midcareer artist with a long resume, she understands how to network and she has the contacts to do it well. Because she’s secure in her career, she knows that sharing information or recommending someone will not diminish her achievements. On more than one occasion she has given my name and website to one of her dealers. I have done the same for her. Result: I’m with a gallery on her referral, and she on mine. We’ve each expanded our careers that much more by the simple act of mutual support.It doesn’t always have to be quid pro quo. Eight years ago I wrote a book on encaustic painting, the first contemporary treatment of the topic. I showed the work of 50 artists. A number of them invited me to exhibit with them in subsequent shows. I loved that! And many of the artists who teach invited me to their institutions to speak. I’ve been a “visiting lecturer,” a “visiting artist,” a “distinguished visiting lecturer” (my favorite title), and an “artist in residence.” The jobs lasted from an afternoon to a week. As a working artist I really appreciated these opportunities when they came. (Image from metanexus.net)

.

Reciprocating at the Same Level

As I write “same level” I’m thinking of an off-the-wall exception: the man who traded a paper clip for a house. But typically reciprocity works best when the parties are at the same level of achievement—and have an equal degree of willingness to share—even if the quid is not the same as the quo, as I described in the previous paragraph. Here’s another example: I recommended my friend Jackie for a good exhibition in the Midwest; sometime thereafter she recommended me for a teaching gig in the Northeast. How cool is that?

.

If an emerging artist were to invite me to show at a tiny academic gallery in Podunk, I’d appreciate the gesture but have no reason to accept. But I'll bet an emerging artist in Podunk would jump at the chance. That’s one reason I always encourage emerging artists to establish their networks early on and to be generous with situations and opportunities. As they all grow in their careers, the reciprocal opportunities get better.

If an emerging artist were to invite me to show at a tiny academic gallery in Podunk, I’d appreciate the gesture but have no reason to accept. But I'll bet an emerging artist in Podunk would jump at the chance. That’s one reason I always encourage emerging artists to establish their networks early on and to be generous with situations and opportunities. As they all grow in their careers, the reciprocal opportunities get better. ..

Teaching, Mentoring, Consulting

.

What If You’re Not in a Position to Reciprocate?

It happens. Life is not a giant tit for tat. But just because you don't reciprocate in kind doesn't mean you don't respond.

. Were you curated into a show? Acknowledge the curator in your promotional efforts. That promotion could be as valuable for the curator as for you. And by all means note the curator on your resume

. Did someone in your field write you a letter of recommendation or reference? Thank them, of course, and keep them in the loop, even if it’s to say, “Despite your generous words, I was not successful in getting the grant.” And if you do get the grant, let them know first. If it's a hefty chunk of change, treat them to lunch at a nice restaurant. (Lunch: when the same good food you get for dinner is half the price.)

. Did you get a great review? I’m not from the school of good-review-merits-a-small-painting (and neither are reputable journalists), but a thank you is never inappropriate. Down the road maybe you’ll find an opportunity to invite that critic to speak or do an end-of-semester crit, with honorarium—or recommend that critic to someone who’s in a position to do so. This is not only a good thank you, its good networking for the both of you

. A note about speaking invitations: Don't assume critics and curators (or even dealers) are rolling in dough. Most are freelance and/or poorly paid, so a visiting artist gig that pays a decent fee is a lovely reciprocal gesture

. Did a more career-advanced artist help you with a statement and resume? Thank her or him. But don’t then use your newly polished resume to pursue all the same galleries that the mentoring artist is in, the same teaching opportunities, or any other venue that that artist spent years cultivating

.

As the previous example suggests, it would be grossly unreciprocal to abuse a generosity. How far to go with what you’ve been given? To be honest, it's a gray area. Ambitious people do appreciate ambition in others. But if you feel uncomfortable telling a mentor or adviser what you are doing/have done, you’ve probably abused their generosity. And if you as an adviser feel have been taken advantage of, you probably have.

.

Reciprocity is a valuable career tool. In its ideal incarnation it's like the t'ai chi symbol at left, which unites the giver and the taker in reciprocity.

Reciprocity is a valuable career tool. In its ideal incarnation it's like the t'ai chi symbol at left, which unites the giver and the taker in reciprocity..

Just be wary of the pathologically ambitious; they’ll suck you dry and never offer a drop in return. You'll hear about them through the art network: "Oh, the one who sat next to me at lunch and asked too many questions," or "He came for a studio visit and now I'm seeing 'my' paintings in his show"--that kind of thing. Best to let them find their own way.

.

What are your comments and stories of reciprocity?

.jpg)