Welcome to The Illusive Eye, at El Museum del Barrio through May 21.

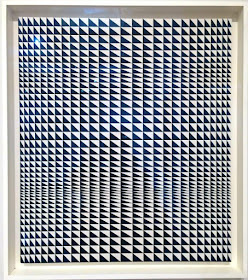

Left: Carlos Cruz-Diez, Venezuela: Psysichromie 321-B, 1967, plastic, cardboard, acrylic, wood; Tadasky, United States via Japan:

#B-115, 1964, oil on canvas

#B-115, 1964, oil on canvas

El Museo del Barrio

El Museo del Barrio is at the northernmost end of Fifth Avenue's Museum Mile, which starts at 82nd Street and ends here on 104th. If you’re not from New York City, or you’re not Hispanic, you might not have visited El Museo. That would be a mistake, because it’s a terrific institution. While its mission is to “present and preserve the culture of Puerto Ricans and all Latin Americans in the United States,” it has mounted exhibitions that anyone interested in contemporary art would enjoy. I have a soft spot for the place because in a show of Latin American artists some years ago, not only did it exhibit a number of paintings by Frida Kahlo, it introduced me to the sculpture of Gego, whose work you’ll also see here.

Detail of the Tadasky, which mesmerizes, and

the Cruz-Diez, which rewards you with closer viewing

The Illusive Eye, an international survey of Kinetic and Op Art curated

by El Museo's director, Jorge Daniel Veneciano, looks at the “optical sublime," works that pleasure

the eye in a variety of ways: via mandala-like shapes, optical tricks, kinetic

works, color, and shadow. With a few exceptions—like Josef Albers, Bridget

Riley, Victor Vasarely—the works on exhibition are primarily by artists from Latin and

South America. Well known in their own countries, they are less so here. Shame

on institutional art history for being so stingy with its purview and on the

museums which should have shown more broadly but didn’t.

As Veneciano remarks online, “We revisit and celebrate the innovations of the MoMA exhibition [The Responsive Eye] and flesh it out with the Latin American dimension that it lacked.” Like The Geometry of Hope, which was shown at NYU’s Grey Gallery in 2007, this is an opportunity to immerse yourself in a visual experience that broadens your art historical horizons as well.

As Veneciano remarks online, “We revisit and celebrate the innovations of the MoMA exhibition [The Responsive Eye] and flesh it out with the Latin American dimension that it lacked.” Like The Geometry of Hope, which was shown at NYU’s Grey Gallery in 2007, this is an opportunity to immerse yourself in a visual experience that broadens your art historical horizons as well.

We're standing in the anteroom with the Tadasky to our left. In the distance: paintings by Jean-Pierre Yvaral, left, and Almir Mavignier, with a kinetic and transparent sculpture by Julio Le Parc, We're going to walk counterclockwise around this room

The exhibition takes place on the first floor galleries of

the museum: a small anteroom with the Vasarely and Tadasky, and four spaces that you walk through successively,

as well as one small room that is vertiginously thrilling. I took so many

photographs that this report is in two parts. Part One here takes you through

the anteroom and into three rooms, with a peek into the fourth. Part Two, which I’ll

post next week, will take you into the rest of the galleries and then walk you

back out.

Almir Mavignier, Brazil: Convex Rot-gelb-weiss (Convex red-yellow-white), 1967, oil on canvas

Detail below

Jean-Pierre Yvaral, France: Variation Sur Le Carre (Variation on the Square), 1959, acrylic on canvas,

This is a gallery that I found satisfying in its materiality and color. Most of the paintings are square, hewing to formal ideas of composition; the sculptures converse in their openness.

Foreground: Julio Le Parc, Argentina: Continuel Mobil Transparent, 1960, stainless steel, acrylic, aluminum, filament. A Vasarely, glimpsed in the far corner, is shown below

Victor Vasarely, Paris via Hungary: Napaura, 1975-78, acrylic on canvas

Jesus Rafael Soto, Venezuela: Cubo y Extension (Cube and Extension), 1971, wood and metal

With Soto's sculpture as our landmark, we continue around the gallery with Tony Bechara on the far wall and artist to be identified, left

Tony Bechara, Puerto Rico: 125 Colors, 1979, acrylic on canvas,

Detail below

Artist to be identified and Richard Anuskiewicz

Richard Anukiewicz, United States: Union of the Four, 1963, oil on canvas

Detail below

This panorama was shot from the far end of the gallery. We're going to walk its length to enter the next gallery. Before doing so, we'll look at the works, shown below, on either side of the doorway. (Click pic to enlarge)

Horacio Garcia Rossi, Argentina: Progression, 1959-60, oil on canvas

Bridget Riley, England: Straight Curve, 1963, acrylic on board

View of the Garcia Rossi and Riley with a peek into the next gallery, whose walls are painted black

In this gallery the focus is on central core imagery. Here, two by Eduardo MacEntyre, Argentina.

Below: Pintura Generativa Transparencias (Generative Painting Transparenies), 1965, oil on canvas

Moving our eye past the doorway that leads to the next room, we see ink-on-paper drawings by Ernesto Briel, which bracket a sculpture in the distance by Julio Le Parc. The Riley painting is on the outside wall

Above, Ernesto Briel, Cuba: Nebulosa; below, Ruptura del circulo in foreground; both 1969

Let's look into the third gallery. That's a Frank Stella painting in the distance. But turn your attention to the right wall, which is seen here in sharp perspective

That same wall is viewed below from a better angle. I've focused on two Constructivist works, which you see as you scroll down

Above and below, Ludwig Wilding, Germany: both Untitled works, screenprint on Plexi, are from 1967 and 1965 respectively

Now we turn to the left wall. From left, Norberto Gomez, Argentina: Sin titulo (Untitled), 1967, wood and paint; Gego, shown below; and Frank Stella

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Venezuela via Germany: Boceto para escultura en el edificio del Banco Industrial de Venezuela (Sketch for a sculpture in the Industrial Bank of Venezuela building), 1961, iron and paint

Frank Stella, United States: Tetuan II, 1964, fluorescent alkyd on canvas

The Stella leads visually to a long wall that connects this gallery with the next one. That's Max Bill's diamond-shaped painting, and the great Carmen Herrera's tondo, which I'll show you shortly.

Below: a detail of the pencil lines containing the stained areas of color. (You can see that the fluorescence has disappeared)

We're stepping back to take in the long wall that leads to the next gallery

Hermelindo Fiaminghi, Brazil: Cor-Luz, Superposiçao de Quadros em Transparencia (Color-Light, Overlapping of Transparent Frames), 1961, tempera on canvas

I love the conversation with the Albers, below

I love the conversation with the Albers, below

Josef Albers, United States via Germany: Study Homage to the Square: Growing Mellow, 1967, oil on Masonite

This wall continues into Gallery Four, leading your eye all the way into Gallery Six, but for now let's take a closer look at the diamond-shape painting by Max Bill, Germany, in the foreground, and a tondo by Carmen Herrera

Below, Carmen Herrera, United States via Cuba: Tondo: Black and White II, 1959

(Now 101 years old, Herrera had her first solo at El Museo in 2008. A retrospective of her work will take place at the Whitney the fall.)

Another view of the wall, which includes at far left the relief by Edgar Negret, Colombia

For this panoramic view I stood in Gallery Four. You can see Negret and Herrera in the distance at right and how the wall flows to contain an Albers (black), Judith Lauand (green), Lolo Soldevilla (small black) and a section of a Gego wire sculpture in the foreground. (Click pic to enlarge panorama).

You can see these latter works, and the rest of the exhibition, in Part Two.

Wonderful post, of a rich artistic language. We know most of the artist from living in south america where artist are separated so much by style but rather Quality is Quality

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for the wonderful post!

ReplyDelete