Robert Mapplethorpe, Louise Bourgeois in 1982 with Fillette (1968, latex over plaster)

.

Given the penile propensities of the art world, Bourgeois was ignored in the early years of her career while her male contemporaries went on to acclaim and success. But championed by the feminists of the New York art world in the 1970s, and then embraced by such curatorial powerhouses as Robert Storr, she became well known as she entered her seventies. She’s the most contemporary near-centenarian, and certainly the most productive, we have ever seen. (And her late-in-life fame makes her something of a patron saint for midcareer artists who have yet to receive their own recognition.)

Like Picasso, she has embraced and mastered a staggering number of mediums, each in service to a wide-ranging vision. But where Picasso’s work was about suffering on a large scale (Guernica) and sex at an intimate level (just about everything else), Bourgeois’s art is about personal pain and a sexuality that is less about personal intimacy and more about eroticism on a grand scale.

Installation view of Spider Couple, Untitled, and Untitled at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2008; © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation New York . Photo: David Heald

.

For the artist's spectacular career retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum of Art in New York City, simply titled "Louise Bourgeois," the rotunda is dominated by two spiders locked in a pas de deux—though it’s unclear if it’s a dance of love or hate, life or death. Actually, you're not really sure there are two spiders until you see them from the top of the ramp.

There are two enormous cast aluminum sculptures suspended from the oculus whose knotted forms are informed by a spiral and whose reflections are of the spiral ramp, which in the several times I visited the exhibition was always crammed with people. (Most of the images in this post are courtesy of the museum, which shows the exhibition mercifully free of the actual hordes in attendance.)

Above, installation view of Spider Couple, Untitled, and Untitled at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2008© Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation New York. Photo: David Heald

Below, the cast aluminaum spirals, suspended from the oculus

The exhibition starts with her earliest work on the lower level, and as you move up the ramp, the work gets more autobiographical, so it helps to know a few facts about Louise Bourgeois:

. She was born in 1911 in Paris

. Her mother was a tapestry weaver

. Her parents ran a tapestry repair business out of their large home in the provincial town of Choisy, south of Paris

. The child Louise would help out when small hands were required

. Pere carried on with the live-in nanny under the roof of the home he shared with his family

. She has been angry at him all these years for what she sees as a betrayal of herself and her mother, and the pain of that betrayal has been something of a muse

. She visited Brancusi's studio when she was a girl. Here's part of the "Brancusi" entry in the catalog: "His room was full of wood beams, and I can tell you where he got them. The big boats would come from Dakaar, Africa, and those beams were the ballast. . . The beams were often left on the banks of the River Seine."

. She studied art in Paris from 1933-1938;Fernand Leger was one of her teachers

. She married the American art historian Robert Goldwater in Paris in 1938 and moved with him that year to New York City

. She raised three sons and made art in domestic spaces, working in the basement and storing her art in the dumbwaiter of her Chelsea brownstone

. Some early work, which consists of scraps of wood, was made on the roof of her building, which the artist used as a studio. Indeed, bits of cedar from an old water tower are incorporated into that early work

. Her first solo, of 12 paintings, show took place in New York City in 1945

. "Until the late 1970s, offers of exhibitons were few and far between," writes Frances Morris in the opening essay to the catalog that accompanies the show. She was embraced by the feminist artists of that period, after which, notes Robert Storr, she became more vocal about the specific source of her pain

. She moved into a large studio in Brooklyn in 1980, which allowed her work to get larger

. Her longtime studio assistant (30 years and counting) is Jerry Gorovoy, himself an artist

. In 1982 MoMA gave her a retrospective

. She's represented by Cheim & Read in New York City, where her work is regularly exhibited in solo and thematic group shows, and at the various international art fairs

. Her work is in collections at major museums internationally

. If the films about her are any indication, she's ornery and impatient. At the same time, the legendary Sunday Salons at her Chelsea brownstown are a model of generosity to artists

. She’s 97 and still at it. Indeed you can sometimes walk by that brownstone on 20th Street, between 8th and 9th Avenues and see her, through the window, working at a table in the front room

Let’s walk up the ramp, shall we?

Femme Maison, 1947, ink on paper, 36 x 14 inches

Bourgeois's earliest works were paintings and drawings, so this is what's installed at the beginning of the ramp. Several works show the combined image of woman and house. I remember Femme Maison as a strong feminist image in the 1970s. Given that home and work were intertwined from the artist's earliest days, and that this drawing was probably created in her home studio, Femme Maison (literally Woman House) very likely has much more in common with Womanhouse, the Judy Chicago/Miriam Schapiro project at Cal Arts than with housewife, another meaning of Femme Maison. (Though apparently the task of raising the children fell to her.)

Above and below, installation view of Personages at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2008© Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation New York

Photos: David Heald

Below, in the far corner, The Blind Leading the Blind

Louise Bourgeois, The Blind Leading the Blind, 1947-1949, painted wood; 70 3/8 x 96 7/8 x 17 3/8 inches

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© Louise Bourgeois. Image courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum

Installation view of "Louise Bourgeois" at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2008; © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation New York

Photo: David Heald

Below, the artist with Femme Volage (the sculpture above that's farthest away on the ramp) The photograph, from the Louise Bourgeois Archive, is from the mid-1960s. The work, 1951, is in the collection of the Guggenheim

The sculptures from the series directly above were made when Bourgeois used the roof of her building as an alfresco studio. She incorporated scraps of the wood she found up there, including castoff cedar shingles from the water tower, a feature of most city buildings, which she painted. I love these works for their scale and materiality, and for their straightforward construction: strung like beads, except vertically on a metal or wood spindle.

The Blind Leading the Blind, the most minimalist of the work from this period, is one of my favorites. (It is not stacked but the construction is also straightforward.) There are other sculptures, totemic stacks of geometric shapes, that I love equally, but the Guggenheim did not include them as part of their press materials, and no photography was allowed (I tried).

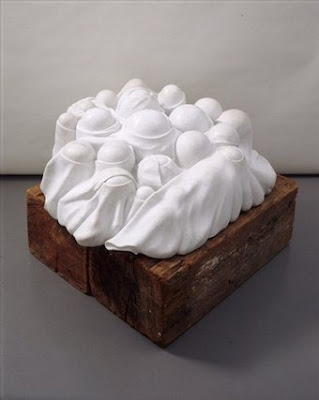

Cumul I, 1968, marble, wood plinth, 20 1/16 x 50 x 48 1/16 inches. Attribution au Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris. © Louise Bourgeois, courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum

.

Below, Louise Bourgeois in 1990 with her marble sculpture Eye to Eye, 1970. Photo: Raimon Ramis, © Louise Bourgeois, courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum

As we walk up the ramp, the shapes become more biomorphic. Materials are marble and metal, as well as favorites of that time, like latex. Travel and politics were most certainly an influence on her work. Bourgeois took her first trip to the quarries in Pietrasanta, Italy, in 1967-68. Her biomorphic work became more overtly sexual as she aligned more closely with the Women's Movement in the 1970s.

.

Arch of Hysteria, 1993, bronze, lifesize. Image taken from Internet

The lean, angular frame of Bourgeois's longtime assistant, Jerry Gorovoy, provided the form for Arch of Hysteria, the exquisitely graceful (or painful, depending on how you look at it) bronze sculpture of a naked male figure bent backward and hanging by a thread. Hysteria was long thought to be a "women's malady," so there's a lovely irony in the use of a male body. Equally lovely: the pose is very likely a calming dhanurasana, yoga bow pose, anything but hysterical.

Two installation shots: with the hanging spirals above, and with a view of Bourgeois's cells and fabric sculptures below. Both images courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum

.jpg)

Bourgeois in her Chelsea home with the same three pink cloth figures visible on the upper left ramp of the installation image above

.jpg)

Above, Cell (Choisy), 1990-1993, pink marble, metal and glass; 120 1/2 x 67 x 95 inches. Photo: Peter Bellamy, © Louise Bourgeois, courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum

Below, Red Room (Child), 1994, mixed media, 83 x 139 x 108 inches. Photo: Marcus Schneider, © Louise Bourgeois, courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum

.+LB.jpg)

Red Room (Child) is dreamlike and surreal, with fact and metaphor interwoven in ways that are entirely known only to the artist. The two pairs of hands on the pedestal in the center of the image are carved from red casting wax, as are what appear to be viscera at the right of the frame. Hands and fingers are, of course, intimately involved with warp and weft, the manipulation of which was the family business. But given the artist’s pain at her father’s affair, those hands suggest not just work but a tender touch and its absence. Red is blood, life, heart, love, heartbreak. Those cones and spools of thread simply reinforce that tangled emotional web.

.jpg)

Louise Bourgeois in the studio of her apartment at 142 East 18th Street in New York, circa 1946. Photo: Louise Bourgeois Archive, courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum

A concurrent show, A Life in Pictures: Louise Bourgeois, in the Sackler Center at the Guggenheim, consists of dozens of photographs selected from the artist’s archives, such as the one above. I assume these will travel with the show.

Read the Book

The exhibition is accompanied by a beautifully illustrated catalog, Louise Bourgeois, which is set up like a glossary (Dreams, Guilt, Old Age, Religion, Spider are a few of its numerous entries). It’s essential reading for any one with an interest in a towering talent whose life is nowhere as neatly arranged as this book.

See the Movies

. The exhibition features selections from the 1978 film, Confrontation, as well as several other films of Bourgeois at home and in her studio in which she talks about her work and reveals some quirky habits (something of a germophobe, she irons each section of The New York Times before she reads it). You also get to hear from her longtime assistant Jerry Gorovoy. (Man, everyone needs an assistant like him!)

. Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress and the Tangerine, a film showing independently of the exhibition, directed by Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach. I don't imagine it will turn up at your local mall, but it should have an arthouse run.

And More

This link to PBS offers several slide shows

The images for this post come primarily from the Guggenheim Museum, with a few taken from the Internet. I intend no disrespect in reproducing copyrighted images taken from the Internet. This is a non-profit blog. The information come from wall texts, my own observations, and in a few noted instances, from the catalog. .