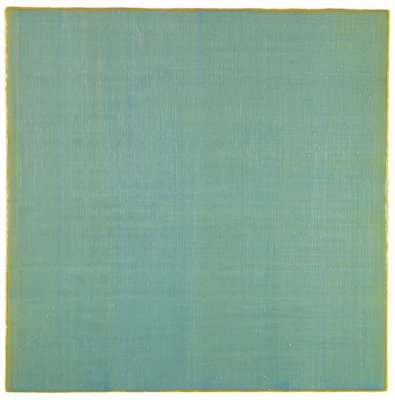

Above, from left: Uttar 294, 36 x 36 inches; two paintings from Vicolo, each 12 x 12 inches; and an installation of Silk Road paintings, each 12 x 12 inches

Above, from left: Uttar 294, 36 x 36 inches; two paintings from Vicolo, each 12 x 12 inches; and an installation of Silk Road paintings, each 12 x 12 inches

While the actual painting for an exhibition is finished by the time the exhibition is installed (though sometimes just barely), there is much to be done after the fact. On Saturday, a few hours before I gave a talk about my work to a nice turnout of artists and collectors, I shot the installation. Yesterday I edited and Photoshopped the pictures, and today Cate McQuaid's review, "A Clever Pairing," appeared in The Boston Globe. I've excerpted her review below:

"Wax and rubber have certain things in common--a tactile similarity, a translucence--that make the two solo shows by Joanne Mattera and Niho Kozuru at Arden Gallery a clever pairing.

"Mattera's encaustic paintings involve pouring layers of pigmented wax one over the next, building up and scraping away to create pieces of brilliant color that catch the light in surprising ways. She lays her emotive tones over grids, bringing order to the expressiveness. Her understated, lovely "Silk Road" series features several foot-square panels, each monochrome, and each bearing the texture and luminosity of silk.

"In her "Uttar" series, she borrows tones from Indian miniature paintings. "Uttar 295" sports a checkerboard of blues with an occasional watery rose. The squares drip, leaning into one another like keening women at a funeral.

" Mattera's stacked lipstick reds appear in columns in "Uttar 295 (Ciel Rouge)." It hangs beside Kozuru's "The Rising Column," made of cast red rubber; the two make a gorgeous installation. "The Rising Column"... shares not only the soft texture of Mattera's work but the wonderful conflation of crisp, traditional form with luminosity and emotional juiciness."

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Uttar 294 (Ciel Rouge), 48 x 67 inches; foreground: Niho Kozuru, Rising Column, cast rubber

Uttar 295, encaustic on panel, 36 x 36 inches, 2006