.

Say you’ve been contacted by a reporter to talk about your work in conjunction with an exhibition or open studio, or any kind of project you’re involved with. Do you know how to handle an interview?

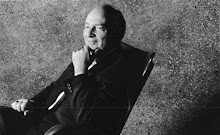

Above and below, talking to the press. (These images from the Internet)

.

The process seems simple enough. The reporter asks questions: How long have you been an artist? Tell me about the show (project, event)? Who else is involved? How did the show or project or event come about? You respond enthusiastically.

Then maybe you break for coffee. The reporter's notebook gets put down and you relax. The conversation slides around to an arts administrator in your city who just got passed over for a promotion, or to an artist you both know to be difficult. You're chatting informally so you respond with a less-than-flattering anecdote about the administrator or share a bit of gossip about the artist. Back in interview mode, the reporter asks you, “Would you show me your process? You’re uncomfortable with sharing trade secrets, or maybe the studio is not set up for that kind of show and tell, so you demur. No problem, says the reporter.

The article comes out. You’re portrayed as a gossiping blowhard who’s eager to tout your achievement but secretive about your process. That’s an extreme example, but it happens.

My day job for 20 years was as an editor and writer, so I feel confident sharing these tips with you:

As long as you’re talking to a reporter, you’re on the record

It doesn’t matter whether the tape recorder is running or not, whether she’s taking notes or not. If it’s an interview, what you say is fair game for the reporter--and that includes art bloggers, many of whom have significant and substantial readership. The good news is that if you’re being interviewed, it’s probably for the arts section, not for national news (unless you're a certain well-known artist who has had some copyright issues), so you if you keep to the topic at hand—you, your work, the project—you should do just fine. This is true whether you’re being interviewed in person, over the phone or via email. Yes, you can say “off the record” if you don’t want something reported, but why say it if it’s not meant for publication?

Want to be quoted correctly?

Keep your answers short and clear. Don’t digress. Speak at a slow-normal pace; rapid-fire speech makes it hard for the reporter to take notes, and on tape it can make you appear manic. If you’re mentioning unusual names or titles, jot them down on a small sheet of paper and give it to the interviewer at the end of the interview. If you haven’t been interviewed before, or if you’re a little nervous about the interview, do a mock Q&A in front of the mirror; this sounds silly, but it’s a good way to get comfortable with what you want to say and how you want it to sound. The better the quality of your information, the more likely you are to be well represented.

Be interesting! Have a couple of good sounds bites

From the reporter’s point of view, a boring interview can sound like blah blah blah blah blabbity blah. I once did an interview with the emerging artist son of a famous painter. The guy was a dull as proverbial dishwater. Nothing I asked him elicited anything interesting or quotable. The fact is that he was a boring guy with boring work who was mildly consequential only because of his dad. God, I was glad to get out of there! Another artist I intervied for a feature was not particularly interesting personally, but his work was and his passion for it was; it was a lively interview that resulted in a good article which allowed that passion to assert itself on each page.

One time, I interviewed a florist-to-the-stars for who was so quotable that what was supposed to be a short item turned into a feature with plenty of anecdotes, pullquotes and pictures. And then there was the well-known artist I interviewed in his Lower East Side studio. I did my homework and he responded with stories, pulled out work to show me, and talked about many of the paintings in his studio, including a now-iconic series that was in progress at the time. That was a great interview!

Writers need a good lead and a good kicker—a juicy quote or comment to end the story. Your passion and knowledge will provide them. Indeed, if you can provide interesting information for each point you wish to make, the interview pretty much writes itself. Relatedly . . .

Be prepared to steer the discussion

Small local or regional publications may not have full-time arts writers, so a general assignment reporter—one with little understanding of art, and possibly no understanding of your work in particular—may be assigned to interview you. If the conversation heads in a way that you know will not serve you well, steer it over to where you want it to be. Offer an anecdote, or direct the reporter’s attention to work that you wish to talk about.

Sometimes a photographer or videographer comes with the interviewer. Draw their attention to the work you’d like them to shoot—not by saying, “This is what I’d like you to photograph,” but by a more enticing lead in: “Let me show you my newest work" (reporters love a scoop), or "I believe this is the piece that secured my grant." Or, "See this detail . . . ?" And then go on to focus your attention and theirs on a particular painting. Put away anything you don’t want to be seen. You can’t control what's written about you, but you can control what you offer to the writer.

Appearance matters

If the interview is in your studio, you’ll look ridiculous in your dress-up clothes; if your interview is in their studio, you’ll look ridiculous in your painting clothes. And you may not like what I’m going to say next, but women are always held to a higher standard in terms of appearance. You can ignore that if you want to, but that's the cold, hard fact. Just look at the pictures above. The interviewee in the top picture, dressed understatedly in a clean silhouette and solid color, will stand out for what she says and for the work she has done, not for how she's dressed. If you're Shepard Fairey, you can dress as you wish--though you notice his interviewer is wearing a suit.

Send the reporter off with a small package of information

Standard presentation materials are usually sufficient: resume, statement, a CD with a few images. Make sure the images are titled. Include a business card so the reporter can contact you if she has follow-up questions.

Don’t demand to read the piece before it goes to press

That’s not going to happen. If the topic is unusually technical, a reporter—or perhaps someone from a magazine research department—will read you specific passages to confirm the correctness of the information. (Books are different because there’s a longer lead time. By all means ask to read the materials about you. Some writers will accede, others won’t, but no writer is going to offer, so you’d be smart to ask.)

Send a Thank You note

Unless the writer did a real hatchet job—and despite my opening worst-case-scenario, that’s not likely—send a note of thanks for the piece, even if there's a misquote or two. Any medium is fine: email, postcard, handwritten note. Writers change jobs, some become editors and may be in a position to assign stories. Everyone remembers the interesting artist who remembered them.

Unless the writer did a real hatchet job—and despite my opening worst-case-scenario, that’s not likely—send a note of thanks for the piece, even if there's a misquote or two. Any medium is fine: email, postcard, handwritten note. Writers change jobs, some become editors and may be in a position to assign stories. Everyone remembers the interesting artist who remembered them.

Do you have an interview story? Share, share!

. .

. .

.

.

.

.